|

Last week’s post took a look at the etymologies of headwear, so this week we’ll move south a tiny bit to take a look at three things worn on the face.

Lately, the veil has received a lot of attention. The noun veilcame into English in the late 1300s from the Anglo-French word veil, which meant both head-covering & sail. This came from the Latin velum, sail, curtain or covering (which, intriguingly is not related to the English word vellum). Both mask & mascara have their roots in the Middle French word masque, a covering to hide or guard the face. This came from a Middle Latin word, masca, meaning specter or nightmare. Nobody’s certain where the Middle Latin came from, but it may have its roots in the Arabic word maskhara, buffoon or mockery, or possibly from Catalan, maskarar to blacken the face. It may even have come from the Old Occitan word masco, which means both witch & dark cloud before the rain comes. Grin showed up in Old English as grennian, to show the teeth in pain or anger. Many Germanic languages had/have related roots: Dutch, grienan, to whine; Old Norse, grenja, to howl; German,greinen, to cry. It wasn’t until the late 1500s that the word grin began to be the sort of thing one might want to see on a friend. Dear followers, please contribute to next week’s post by using the comments section to suggest other items, treatments or expressions that might be worn on a face. My thanks go out to this week’s sources, Etymoniline.com, Merriam Webster, The OED,

0 Comments

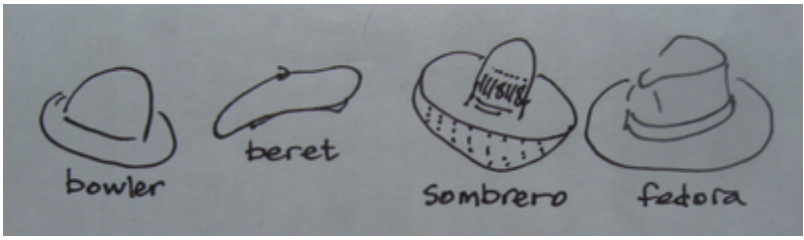

This week is an etymological tip of the hat to headwear.  Hat comes from the Old English word haet, head covering, which came from a Proto Indo-European word meaning cover or protect. Cap is also came from Old English. It started as caeppe, a hood covering or cape. This word came from the Latin word caput, head. In English it only referred to women’s head coverings until the late 1300s, & is, not surprisingly, related to the French word chapeau. Though most modern Americans associate the fedora with noirish characters of the 1930s, the term initially referred to a hat worn by a woman – Sarah Bernhardt -- who in 1882 at the time of her fascination with soft-brimmed, center-creased hats, was playing the part of a Russian princess in a Victorien Sardou play, Fedora. Bernhardt’s fashion choice inspired a rash of fedora-wearing women’s rights activists. Some years later, those 1930s noirish hoods liked the look, too. Though the derby was being manufactured in the US as early as 1850, it didn’t earn its name until twenty years later, when that particular style caught on across the pond at the Derby horse races. Sombrero entered English in 1770 from Spanish sombrero, a broad-brimmed hat. It heralds from sombra, or shade, & initially described a parasol or umbrella. Beret entered English in 1827, from the French word béret. Before landing in the French language, beret travelled through Bearn, Old Gascon, Late Latin, & Middle Latin. Its Middle Latin form is the diminutive form of birrus, a large, hooded cape. Etymologists don’t agree on the beginnings of the bowler. Some claim it was named after J. Bowler, a popular London hat maker of the 1800s. Others trace it back to the Old English grandmother of the word bowl, heafodbolla, meaning brainpan or skull. Those Old English folks really had a way with syllables, didn’t they? Dear followers, did any hat word histories surprise you or cause a wrinkled brow? Please leave your thoughts in the comments section. My thanks go out to this week’s sources, Etymoniline.com, The OED, As we climb the long, slippery slope toward the 2020 elections, news stories become increasingly easy to confuse with political advertisements. Though I’m generally a huge fan of fiction, when it comes to political reporting, I find myself in the Joe Friday camp.

That’s right Ma’am, just the facts. When a news story involves a candidate’s claims of past successes, I expect the claims will be confirmed by the news source, and the results of this fact-checking will be included in the story. By definition, news sources should be involved in verifying their sources, in substantiating claims, in authenticating, & corroborating. This brings me to celebrate once more, the synonyms entries found in any decent, grown-up dictionary. My 1959 Webster’s New World Dictionary offers these synonyms & definitions for verify. These words, I submit, provide a healthy mantra for reporters, readers, listeners & viewers during this election season. confirm is to establish as true, that which was doubtful or uncertain substantiate suggests the producing of evidence that proves or tends to prove the validity of a previous assertion or claim corroborate suggests the strengthening of one statement or testimony by another to verify is to prove to be true or correct by investigation, comparison with a standard, or reference to ascertainable facts authenticate provides proof of genuineness by an authority or expert validate implies official confirmation of the validity of something Dear followers, please respond by either complimenting news sources you’ve found that seem to see the above as part of the day’s work, or mentioning those sources that flagrantly ignore the above responsibilities. You might also suggest other mantras that might help us in these politically polarized times. My thanks go out to this week’s sources, Etymoniline.com, The OED, & Webster’s New World Dictionary of the American Language, 1959. Here’s a thematic dip into the etymologies of some common fabrics.

The word muslin came to English about 1600, from the French word mousseline, which came from the Italian word mussolina, which came from the Italian word Mussolo, a rendering of the Mesopotamian city, Mosul (now in Iraq). It was in Mosul that people wove a luxurious fabric of silk & gold the Italians called mussolilna. Nobody’s quite sure how muslin lost its luster, but by 1872, Americans defined it as everyday cotton fabric for shirts & bedding. Corduroy’s story provides a near-mirror image of muslin’s story. Corduroy entered the language in 1780 & referred to a coarse fabric made in England. Tales are told that it comes from corde du roi, the corde of royalty, but no evidence exists to support this story, & coarse cloth would definitely chap the hide of royalty. Today, corduroy is a durable, cotton fabric with vertical ribs or wales. The word denim entered English in the late 1600s. It came from the French serge de Nîmes, meaning serge from Nîmes (a town in southern France). The word denim was first applied to the trousers we call jeans in 1868. The word canvas made its way into English in the mid-15th century, from the Old French word canevas, which meant made of hemp, from the Latin cannabis. Who knew? Last, & least referred to in this modern age, is the word seersucker, which comes from the Hindi word sirsakir, which came from the Persian shir o shakkar. This term referred to a striped cloth alternating between smooth & puckered textures. Shir o shakkar translates literally to milk & sugar, suggesting that the smooth stripes in the fabric are smooth as milk, while the puckered stripes have a rougher texture. Dear readers, shall we all plan a trip to the south of France, wearing our serge de Nîmes? Or what do you think of bringing back seersucker? Or have you ever met sailors who appear to have had a bit too much experience with, well, shall we say canvas? My thanks go out to this week’s sources, Etymoniline.com & The OED. Seven long years ago, word nerds worldwide were either jazzed or all het up due to Merriam-Webster’s 11th Edition Collegiate Dictionary. The big news has to do with the 97 new words (I promise, I won’t list them all).

The biggest splash was made by – what a surprise – the most titillating words of the bunch: sexting & f-bomb. I agree that these words are notable, but I find myself most intrigued by comparing the dates the “new” words were first introduced to the language to the years they made it into the dictionary. The following “new” words were coined from 2000-2007: bucket list cloud computing geocaching sexting These “new” words hail from the 1990s: e-reader flexitarian game changer gastropub man cave shovel-ready It took these words from the ‘70s & ‘80s over thirty years to be acknowledged: f-bomb life coach obesogenic systemic risk But take a look at the patience of these mighty words: 1959 – tipping point 1939 – aha moment 1919 – gassed 1904 – energy drink 1859 – mash-up 1802 – earworm So, fellow lovers of language, what words do you suggest have been waiting long enough in the usage queue to make it to the next edition of Merriam-Webster?. My thanks go out to this week’s sources, The Mercury News, The LA Times & The Washington Post An earworm is a cognitively infectious musical agent, more informally known as one of those annoying tunes that you can’t get out of your mind.

Though earworms have haunted me my whole life, I promise to refrain from providing lists of likely tunes that will haunt you forever. The word earworm has interested me since it was first introduced to me some time in the late 1960s by an aunt who grew up in Germany during the 40s and 50s. Only a few years ago, most dictionary and etymology websites clearly credited James Kellaris, a Milwaukee professor, with the coinage of the word in 2001 (e.g. this AP story by Rachel Kipp). Others, like this Wikipedia article, credited Robert Frietag (a well-traveled primary teacher) for bringing the term to English in 1993. These Frietag & Kellaris claims curdled my cheese because (thanks to my Aunt Inge) my pals and I have been enjoying the word since I shared it at Columbus Junior High over four decades ago. Today, a search for earworm etymology will produce over 40,000 hits. Thankfully, in the last year, many etymologists have dug a bit deeper, & while praising Kellaris’s research on the phenomenon of the earworm, have de-bunked the myth that he coined the word. I find no arguments debunking the Frietag origin, but I’m, pleased to say that at long last, most etymologists see earworm as a simple translation from the German word ohrwurm. Confusing the issue is the fact that the German word ohrwurm also refers to dermaptera, the lowly earwig, a nasty little bug which has a tendency to make many of us squirm & whose name has inspired stories about earwigs climbing into people’s ears. The whole issue was likely further confused by a practice popular in “ancient times” (I can’t find where), of drying and grinding up dermaptera, then inserting the powder into infected ears as a medical treatment. So I say bravo & brava to hundreds of hard-working etymologists, to Merriam Webster’s Eleventh Edition, & of course, Aunt Inge, for the word earworm. Good blogophiles, feel free to comment on all this hoopla, or share one of your most annoying, most invasive earworm tunes. My thanks go out to this week’s sources, Etymoniline.com, Blue Harvest Forum, Word Origins.org, Wordspy.com, Wiktionary, & Dictionary.com What does etymology tell us about play, sport, & competition?

Sport came into English in the 1500s meaning both a pleasant pastime & a game involving physical exercise. In the 1660s, Shakespeare crowned war-making the sport of kings. By the 1880s the noun, sport, came to mean good fellow in American English, while down under, the word sport grew to become a way to address a man (1935). Play comes from the Old English plegian, to exercise, frolic, or perform music. Its Middle Dutch ancestor, plegan, meant to rejoice or be glad. Some play-based idioms include: mid-1500s to play fair 1861 to play for keeps 1886 to play the ___card 1896 to play with oneself 1902 to play favorites 1909 to play up 1911 to play it safe 1927 play-by-play 1930 to play down 1936 to play the field Also, in 1959 Play-Dough was born. The word compete came to English in the early 1600s. Centuries beforehand, it started as the Latin word competere, where it initially meant to come together, to agree, or to be qualified. In Late Latin competere came to mean to strive in common. On its way through French to English its meaning shifted to mean to be in rivalry with. Good followers, I’m hoping you’ll have something to say about play, sport, or competition. My thanks go out to this week’s sources, Etymoniline.com, Mad Music, & the OED. Most words meaning kiss are imitative of the sound of a kiss, yet these words don’t all sound the same. Could this reflect on the nature of kisses in various cultures, or simply the vagaries of language? Buss entered English in the 1560s and seems to have come from a Welsh or Gaelic word, bus, meaning lip. Buss falls in the imitative kiss-word camp. Robert Herrick clarified buss’s shades of meaning in 1648 (Beware, Herrick shows no modern sensibility): “Kissing and bussing differ both in this, We busse our wantons, but our wives we kisse.” Kiss is another imitative word, with precursors in Dutch, Old High German, Old Frisian, & Norse. My personal favorite precursor is the Old Saxon word, kusijanan. Imitative? Hmm. One must wonder about those old Saxons. Osculate made its way into English in the 1650s from Latin osculari, & means little mouth. Try to say kusijanan with a little mouth. Snog showed up in the language in 1945 as British slang, initially meaning to flirt or cuddle, though over time snog has come to mean kiss. Its origins are a complete mystery. Smack is an imitative term from the late 1550s, originally meaning to make a sharp noise with the lips, then morphing within fifty years to mean a loud kiss. Mwah, meaning either a kiss or an air-kiss, is another imitative term. Mwah came to the language in 1994. Smooch (my personal favorite), arrived in English as a verb in 1932 & a noun in 1942, from the German schmutzen, to kiss, which most likely was born of imitation. I also must admit a fondness for the term Give me a little sugar, which appeared in the script of A Raisin in the Sun in 1959. Though I can find suggestions that this euphemism was in use before 1959, I haven’t been able to verify any. Do these different-sounding kiss words reflect cultural differences? Class reflections? Vagaries of language? Or are kisses & such the sort of magical things we simply shouldn’t analyze too closely? My thanks go out to this week’s sources, Etymoniline.com Scriptorama, & the OED. The word eavesdrop has a poetically beautiful etymology.

It comes from Middle English, born of the Old English word, yfesdrype. Eaves are, of course, those bits of a house’s roof that stick out from the house. Historically, the eavesdrip was the line on the ground where the rain or morning dew dripped from the eaves. In time, this became a legal term, used to determine – in part – how close one house could be built to the next house. In time, the droplets falling from the eaves acquired the moniker eavesdrops. Soon after that, nosey people who stood close enough to their neighbors’ homes to hear what was going on inside were called eavesdroppers, since standing so close put them in the eavesdrip. Soon, the British legal system happily applied the term eavesdropper to nosey listeners. Is that poetry, or what? Good followers, what have you to say about this transformation, or about your experiences being eavesdropped upon, or possibly eavesdropping? Writers out there, I would submit that we find more eavesdroppers in fiction than in real life – true or unfounded hogwash? My thanks go out to this week’s sources, Etymoniline.com, RandomHouse.com, The Word Detective, & The OED. I write because I like to write. It stokes my fire, yanks my crank, makes me smile. Sure, parts of the editing process are a real pain, but the pain for me is entirely figurative. Still, I’m intrigued by those who – in order to write – have to open up a vein and bleed all over the keyboard, and then after doing so, they go back and do it again.

Erica Jong wrote, “Writers are doubters, compulsives, self-flagellants. The torture only stops for brief moments.” (1974) Her writing reality was not my writing reality, but it causes me to wonder about that simple five-letter word, write. Etymologically speaking, there isn’t much support for the pain and suffering Ms. Jong and her ilk experience, though at first glance it appears there might be. Both writanan, write’s proto-Germanic grandmother and writtan, it’s Old Saxon grandmother, originally meant “to tear or scratch.” In fact, most the Indo-European languages’ precursors to write referred to carving, scratching, cutting, or vigorously rubbing. These violent-sounding word histories simply reflect on a world without keyboards, legal pads, fountain pens, ballpoints and yellow pencils – a world which required writers to scratch their brilliance into bark or chisel it into stone before it could make its mark on the waiting reader. George Sand, a self-confessed bleed-all-over-the parchment writer, offers this, “The profession of writing is nothing else but a violent, indestructible passion. When it has once entered people’s heads it never leaves them.” (1831) I’m all for the idea that once the passion enters, it never leaves, but the pain and agony simply aren’t a part of the game for me. What do you think? Is writing more akin to cutting, scratching and carving, or is it simply a joy? Thanks to these sources: the OED, The New Beacon Book of Quotations by Women, wordreference.com, & etymonline.com. |

I write for teens & tweens, bake bread, play music, and ponder the wonder of words in a foggy little town on California's central coast.

To receive weekly reminders of new Wordmonger posts, click on "Contact" & send me your email address. Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed